12/22/2020

Enroute

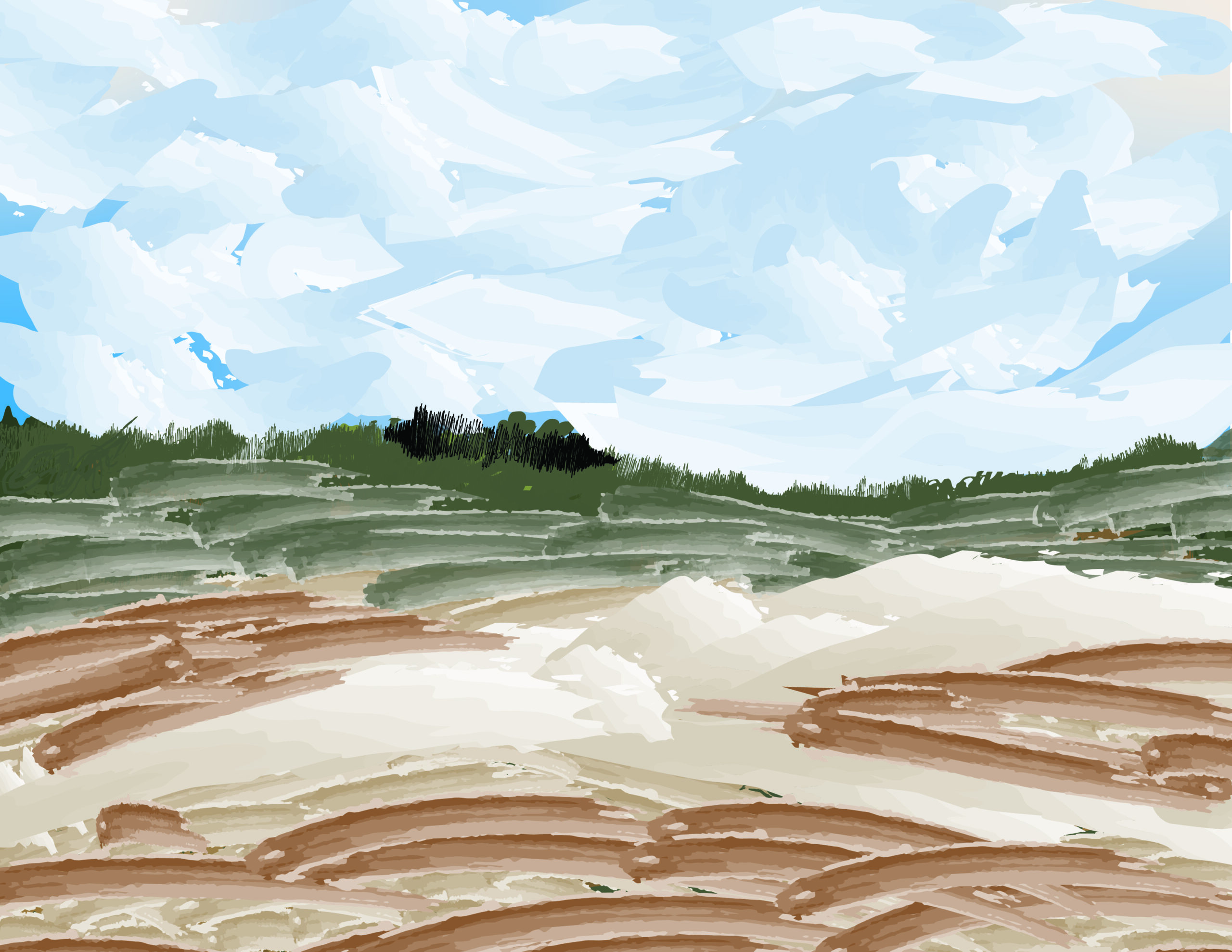

The probox is traversing the dirt roads that snake their way through the thickets and bushes and the wind is blowing in my face, a cool wind – atypical to the usually scalding weather this part of Kenya is used to. Next to me are two other passengers, one sleeping through the bumpy ride and the one between us chipping into the conversation between the driver and the passenger beside him every now and then. “A whole family!!” exclaims the driver when we spot a herd of warthogs with their tails raised scuttling across the road, “Baba, mama, watoto!”

Aqals[1] spring into view sporadically and I am struck by how different the scenery is to that of my childhood. Topographies are fascinating. One nomad, laden with yellow jerricans that once assumedly harboured cooking oils, talks to the driver in Somali and when questioned about the conversation, the driver replies that the nomad was inquiring if there was water where we were from. “But I told them the roads were dry.”

“You know they collect the water from the roads.”

“I once saw a man bathing in the puddle on the road, you can imagine how long it had been since he had last had a bath.”

The co-driver regales us with varying tales:

“You know sometimes I ask my mum why she didn’t give birth to me as a mzungu” he starts another line of story, “I wouldn’t be hustling out here like this. My work would be relaxing on the beach with some nice sunglasses and a drink in one hand, having already donated to orphanages, taken a picture smiling with one or two children, started a couple of NGOs…” and we are all chortling, adding things like, “Oh yes, bora umepigwa mapicha, na uende masafari!”

“But I love my mum!” he concedes, “we just joke around a lot.”

We reach a place that’s really muddy and threatens to halt out journey but the driver, who boasts about peregrinating this route daily, adroitly manoeuvres the probox around, twisting the steering wheel left and right so fast that you’d think he was Vin Diesel, on a grave mission to rescue family. “Lakini I tell you when it rains heavily, this road is unpassable!” my left-to-me exclaims! “Heh, siku ingine it rained and the fare was hiked to a ridiculous 5000Ksh because only Land cruisers could somewhat manage the murky terrains– and even then, even after paying so much for a place that usually goes between 500-1000Ksh, bado utasimama usukume gari ikisimama! – when the car gets stuck, you all get out in that mud and push it and then get back on again.”

“Lakini nakwambia if there is a car that doesn’t care whether it rains or not, whether the roads are impassable or not, it’s a car that’s transporting miraa. Those cars, even after roads have been rendered undrivable by extreme storms, will somehow always arrive in Dadaab!”

“They’ll even arrive before trucks that are supposed to bring medicine and supplies and food.”

“Mi nakwambia the other day we were travelling and we suddenly reached a place where the road had sinked under a pool of water and while all other vehicles were stalling, the miraa driver commanded his turnboy to wade into the pond with a stick (as if they were ready for such an outcome) and measure how deep the water supposedly was.”

“Ati nini!”

“Aki walai, I tell you the guy was told ‘toka enda upime maji!’ and he went, waded into that pool with a stick prodding around and seeing how deep it really was and when he came back with his findings, the driver concluded that it was possible to cross the pond and so off he drove, through the waters that lapped almost to their windscreens, all the way to the other side! Na sisi we were just left there – ati waiting for the sun to dry the road up a little bit more.”

“Miraa drivers are wazimu!” the driver says amid laughter, “but t’s because they also consume miraa.”

“Hata wakati wa lockdown,” our narrator continues, “when only trucks transporting food were allowed in and our of the city, I tell you, miraa cars were going through. Uhuru [the president] alisema pia miraa ni mboga!”

“But you I tell you, you are even driving nicely – nakwambia there was one day I took the bus from Wajir to Dadaab and I tell you I was fearing for my life the whole time. I was holding my seat so tightly thinking – I haven’t died from chronic illnesses, a gunshot, famine, to come here and die because this driver has willed it so?! You know that bus was going so fast hata I couldn’t see the trees, all I see was one continuous stream of trees. That’s how fast the bus was moving, that even the landscape could not be clearly seen, only a blur if you looked through the window. Once I alighted, I vowed never to travel to Wajir again, and most definitely not with that driver!

“Lakini let me ask you,” My left-to-me inquires of the driver, “ Why don’t they tarmac this road from Garissa to Dadaab?”

“Hii watatengeneza kukikosa barabara zingine za kutengenza Kenya!”

They will tarmac this road when there are no more roads to tarmac in Kenya

He is not exactly wrong. This area, termed as the Northern Frontier District (NFD) during British colonial rule, has perpetually been on the periphery of state interests. The NFD was an administrative term assigned by the British colonial government to the Northern and Eastern Part of current Kenya. The NFD spans roughly over an area of 102,000 square miles and currently includes Garissa, Wajir and Mandera and partially Turkana counties. Under British rule, the NFD as borderlands were not only administered separately from the core agricultural districts such as in central Kenya [being arid and lacking in any known mineral resource], but also perceived as being just on the periphery of colonial rule[2]. Not unlike the approach taken by the postcolonial Kenyan government, exacerbated by a secessionist movement not just by the Somalis, but also by other Muslims inhabitants of the NFD in favour of joining the newly independent Somalia Republic. What followed was not only a brutal war[3], but also increased strain between ethnic Somali and the Kenyan government, with increased symbolic and literal marginalization of the NFD.

***

“Lakini even us Christians we have a lot of things we can’t do,” the co-driver says in response to the left-to-me haranguing the driver about strict Islamic rules, “Imagine there are so many things we do that we shouldn’t but you know most people wait until they are about to die before repenting. But I feel like God gets angry at our bullshit and he’ll say ‘kwenda uko! Umelalalala hapa halafu unakuja kutubu! Wewe enda tu Jehanamu mara moja! Unatubu hapa nini?”

“hehehe, nakwambia ukifanyafanya dhambi halafu unaenda kutubu – even God can take your last breath before you are done repenting.”

And this way, with these stories that spring now and then, five people make their way through the aridness, honking at indifferent camels that eat from the high bushes, espying the occasional warthog, and being accompanied by an ostrich jogging along the vehicle.

[1] traditional Somali nomadic portable huts made of wooden branches covered with grass, reed and polythene bags. Aqals are easily collapsible so that they can be loaded on pack animals and moved along with the herds

[2] Cassanelli, Lee: 135. 2010. “The Opportunistic Economies of the Kenya-Somali Borderland in Historical Perspective.” In Borders and Borderlands as Resources in the Horn of Africa. James Currey.

[3] The Shifta War. The conflict was “ between [Somali] ethnic national identity on the one hand, and colonially based [Kenyan] territorial sovereignty on the other”. Read more at: Lewis, I.M: 50. 1963. “The Problem of the Northern Frontier District of Kenya.” Race 5 (1): 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/030639686300500104.